Lagusta Yearwood will be the first to tell you that there’s no such thing as ethical consumption under capitalism—in fact, she does exactly that in a section of her cookbook, Sweet + Salty, entitled “‘Ethical Consumption’ Ha Ha Ha.”

The irony, which is far from lost on her, is that Yearwood is a business owner. She runs three all-vegan shops: the chocolate shop Lagusta’s Luscious and the café Commissary! in New Paltz, and Confectionery! in the East Village, which she co-owns with her best friend Maresa Volante, of Sweet Maresa’s macarons.

As a lifelong anarchist and vegan, Yearwood’s focus is on doing the best she can within a capitalist society, while making unique and creative sweets like tahini meltaways and caramelized onion truffles that manage to charm vegans and non-vegans alike. We chatted with Yearwood about the politics, ethics, ingredients and everything else that goes into her decadent caramels and candies.

One of the things that’s interesting to me about you and your book is how politics are so front-and-center. You talk about running your shops with this sort of queer, anti-capitalist mindset.

I really started out life in the activist world and thought I’d be working full-time for societal change. So it’s strange to me that I own a business, and I always try to run the business with politics in mind. I think when you start a business in a traditional way, you’re looking at the business side of things first and then you try to overlay some political skin on top of things. And that’s really hard to do. But for us, it’s inverted. It’s the bedrock of things.

Considering how many ethical factors there are in sourcing, how do you keep things afloat, financially?

It’s just a lot harder, I guess. Businesses make money off of cheap labor, cheap overhead or cheap food costs. And we don’t have any of those things. We try to run the business efficiently—we’re obsessed with food waste, not only from an environmental standpoint, but because chocolate, for example, is so expensive. So everyone knows if you’re making ganache, you better scrape every last bit out of that bowl.

There are so many individuals and businesses that are vegan, but that’s where their activism ends. It doesn’t extend to the humans involved in the process or other environmental aspects.

That’s so true, and I hate it. I feel like my mission in life is to combat that. I always tried to think of veganism as an umbrella belief about not causing harm, and not just to animals. So I’m always trying to extend what veganism means. It’s just one decision out of so many ethical decisions.

I want to say, though, for a lot of people, veganism is really hard. I have a lot of privilege in that veganism is really easy for me, so it’s not that difficult for me to address other ethical considerations too. And for some people, it really is.

It’s important to have compassion for yourself. Sometimes when you see everything that can be wrong with the entire supply chain of buying anything, it can kind of shut you down. I know we’re not perfect, and there are probably ingredients we use that are not great. We’re just trying to do the best we can within the structure of a commercial business.

RELATED: What to Expect From Eleven Madison Home’s New Plant-Based Meal Box

Even considering where chocolate and sugar come from is really rare among vegan businesses.

That’s why I wanted to have a chocolate shop, to see if I could take this product that has so many ethical implications and try to do it in a good way. It’s a big challenge. We used to use this chocolate supplier that was organic and fair trade, but we watched them grow and I started to get…I don’t know, a feeling in my bones that this was not a company I wanted to be working with. I started asking around among people in the chocolate industry and they were like, “yeah, no, that company’s sketchy.” It’s weird because they appeared to fit everything we stand for, but something just didn’t seem right. And I think I was right, actually.

The weird thing is, we talk about intuition a lot. Every single time I’ve ignored an intuition about someone, I should have listened to it.

Do you do much educating people when they come into your shops, letting them know why you do and don’t do things a certain way?

I think that’s something we could be better about, but if someone is mad that they’re paying $2.50 for a piece of chocolate, I’m not afraid to say, “that’s because we’re not using chocolate that was harvested by child slaves.” That’s just the way it is, and I have no problem saying that.

That said, we have the best, most loyal customer base. I feel comfortable hashing out more complex issues on Instagram, even in situations where we don’t quite know how to handle a sourcing problem yet. I feel like most people in business don’t do that because they want to present as having answers. But I think it’s important to say sometimes that maybe there are no answers and we’re all just trying.

There’s something there about having an image of authoritativeness, or not.

That’s something I think about all the time because of identifying as an anarchist, and being uncomfortable being a boss to 40 people. It’s taken me a long time to reconcile that, and it’s come from my employees pushing me to be the best boss I can be. It’s an interesting line to navigate.

The irony now is that now I’m interested in making the businesses profitable. But I know it’s for the right reasons. Maybe that’s what people say when they’ve been brainwashed by capitalism, but I don’t think wanting to provide better jobs for my employees is a bad reason. The fact is, we can’t do any of the cool things we’re doing if we’re not profitable.

It’s funny that the focus is on making money only now, and not when you first went into business.

I know. I think I really just want to live a good life. I just made whatever I wanted, and people bought it. And to a certain extent it’s still that way, we make what we want, and we’re amazed that people buy it.

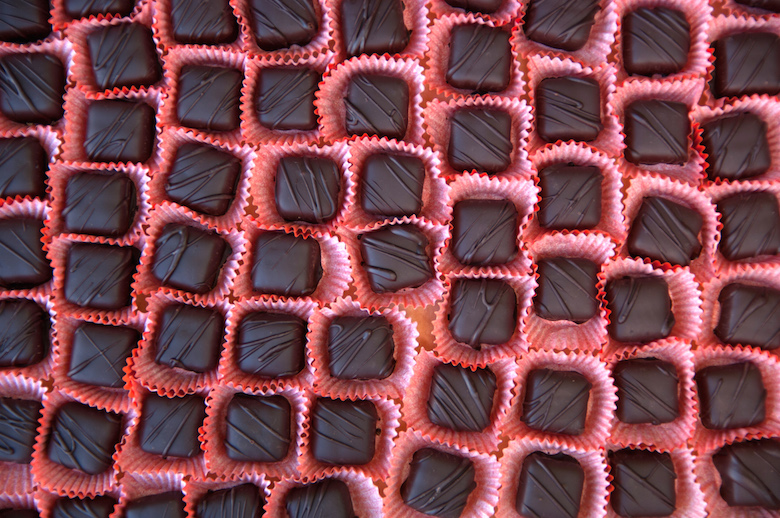

Feature photo shows pumpkin spice caramels, a recipe from the book. Photo courtesy Hatchette.

This story was originally published in October 2019.