We bought the pasteles from Carmen. She was my dance teacher’s mother, a good-natured woman with dyed red hair who ran the desk at the studio and put up with the overzealous moms and young brats in leotards. Come Christmastime, she also became a sought-after maker of the coveted, tightly wrapped pockets of mashed plantain, yucca, pork and spices that are a seasonal Puerto Rican tradition.

There were Puerto Rican dishes that my mom made—tostones, beef-stuffed empanadillas—taught to her by my grandmother, my dad’s mother, who moved to New York City from Rincón in 1939. Pasteles, though, were understood to be more complicated and better bought from an expert. The filling, containing bits of vegetable and tender pork, wrapped traditionally in a banana leaf, was a dream to me.

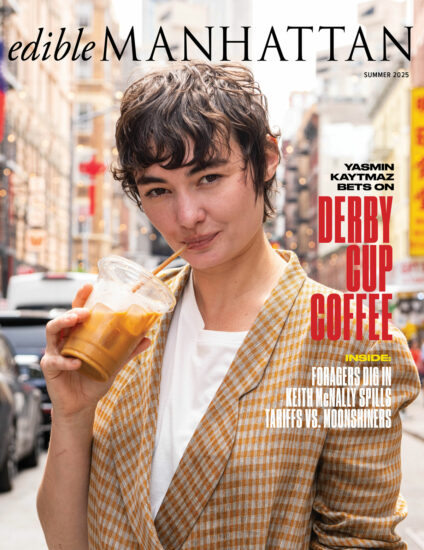

Yet I haven’t eaten one in 20 years. I quit dancing, and then I quit meat. But last November, on a reporting trip to the island, I was presented with a plate at La Alcapurria Quemá in La Placita de Santurce: one pastel, arroz con gandules. I stood to photograph it, to get that perfect overhead angle, and stared at it for a beat too long. In that beat, I went back through time to my childhood, to my dance studio, to Carmen. I saw myself eagerly eating through the ones my mom had bought frozen and then boiled, looking for the meaty bits. Instead of digging in after getting the shot, I waited to be brought a meat-free alcapurria. What could I have remembered if I let myself eat it? When you give up meat, I realized then, you give up a route to memory.

Since then, I’ve thought about creating a meatless version. I know I should sub in fresh tempeh, the way I put beans in my empanadillas, but pasteles are different. There’s a sacredness to them: They take a lot of work, and we want them to be perfect.

There are many ways to make them, and each family has its own take. The dough, or masa, doesn’t contain any corn despite its name; it’s a blend of grated root vegetables and hard green banana. You can add anything you want to the mash: chickpeas, lobster, currants. “I had an aunt who would put raisins in her pasteles, and I wasn’t really messing with that,” Manolo Lopez, owner of Mofongo NY, tells me. “Pasteles are like a rainbow,” Yvonne Ortiz writes in A Taste of Puerto Rico. The filled mass is then folded into a banana leaf or parchment paper and tied up with a string in preparation to be boiled—a gift.

The diversity and their mystery might go hand in hand: No one really knows where the dish came from. “Historians tend to associate the dish with the African culinary influence on the island,” says Dr. Melissa Fuster, an assistant professor of public health nutrition at Brooklyn College who specializes in Latin-American communities. “At the same time, the pastel is similar in preparation method to the tamal found in continental Latin America and Cuba, tied to the indigenous culinary traditions in the region. The masa is usually made from a mixture of green bananas, plantain and yams. Some are made from yucca. These ingredients represent a mixture of African and Taíno ingredients, while the filling—usually pork—is part of the Spanish heritage.”

While they’re eaten year-round, the work they require makes pasteles a labor-of-love holiday dish. “It’s something that you do with your whole family so you can get that bonding with your mom or your grandmother, because it’s a hard technique to do,” says Lopez, who makes an appropriately modern deconstructed version for private catering. “For the special events over here in New York, a lot of people order it because they want to do events that remind them of Christmastime on the island, where you have your arroz con gandules, or rice and pigeon peas, and then you have the pernil, the pork, and then you have the pastel. It’s something that’s in our culture, so you’re born with that and you keep passing it on.”

“It gets handed down fast,” he continues, explaining that—like many of the world’s best dishes—there’s no standard way of making them. “It’s not a recipe, per se, that you can write down and quantify. It’s more about what you saw your mom and your grandma doing—a little bit of this and a little bit of that. And if you ask them, they’ll just say, ‘A little bit of this and a little bit of that.’ They can’t give you a recipe.’”

Making sure you pass it on isn’t easy, though. In her recipe from The Art of Caribbean Cookery, the Puerto Rican author Carmen Aboy Valldejuli has filling, masa, shaping and cooking all in different categories, each with lettered sets of ingredients. There’s even an illustration for assembly. “It’s really tedious and it’s hard work,” Lopez admits. “Nowadays when we make them, it takes forever. But back home, everybody sells them. You go to the neighborhood where your grandma is, and if she’s not making them, you know where you can get a dozen of them.”

“It is more common to buy pasteles from someone else than making them yourself,” Dr. Fuster tells me. “Hence, pasteles also serve as an additional source of income to some Puerto Rican families during the holidays.” When my mom was buying them from Carmen, we were part of a stronger tradition than I’d realized.

The Puerto Rican diaspora is prevalent in New York City, so you’d think pasteles would be more widely known and found; when Fuster doesn’t go back to the island for Christmas, she seeks out a pasteles-maker through community networks. Many, like Lopez, go to Casa Adela at Avenue C and East 5th on the Lower East Side, which has been open since 1976. “It’s that place where you go when you miss Puerto Rican food,” Lopez says. “And they make them there and also sell them by the dozen—pre-order them, though, because they sell out quick.”

Unlike the classic take at Casa Adela, Mofongo NY’s deconstructed version is in line with how younger chefs on the island have been redefining traditional cuisines, presenting dishes in a way that says “fine dining” rather than “grandma’s house.” But all the elements are still there—just with a topping of microgreens.

If there’s no set recipe, no clear origin, and chefs are serving them in a new way, then maybe I can make my own. I’m ready to take what I can from cookbooks, to stand and grate the plantain, season the tempeh, wrap the filled dough in parchment and tie it up like a gift. It won’t be exactly the same as when I was a meat-happy kid, but it will still be Christmas.