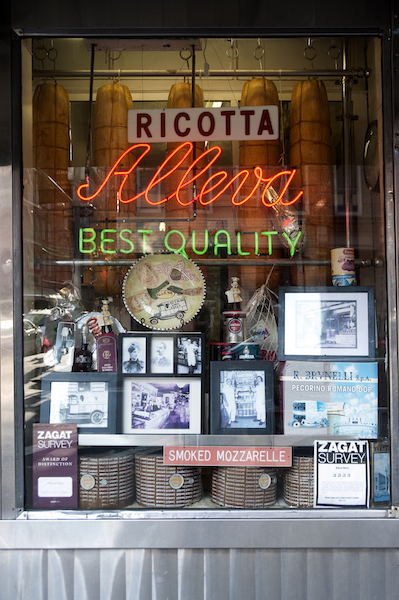

These days few Italiophiles buy ingredients in what’s left of Little Italy. The camera-wielding tourists, the overpriced red-sauce joints, the Chinatown street vendors flinging fish guts to and fro: It’s a far cry from the boot country. But those who persevere past the kitsch and the crowds can be richly rewarded for their efforts with one of the city’s finest culinary delights: Alleva Dairy’s fresh ricotta.

Tucked inconspicuously into a corner refrigerator, it’s easily overlooked in this ramshackle little shop, which is crammed full of edible stimuli like oversize wedges of fontina and provolone-stuffed olives. Ricotta isn’t Alleva’s best-seller, not by a long shot—the 120-year-old business is better known for its homemade mozzarella bobbing in bowls of brine, and their imposingly large wheels of imported Parmesan stacked on the eye-catching cheese counter. But that ricotta should be beloved, because it’s some of the best on this side of the Adriatic.

While other tubs are light and airy, this one’s thick and dense, with a gentle lingering sweetness after each mouth-coating bite. Alleva has had plenty of time to master it. Now run by fourth-generation owner Bob Alleva, his family’s namesake shop is the oldest Italian cheese store in the United States. It opened in 1892, when Bob’s great-grandmother, Pena Alleva, came to America from Benevento, outside Naples, along with the four million other Italians who immigrated to the States between 1880 and 1920. The store has always been on Grand Street, though Pena first curated curds in the building next door, which today houses Piemonte Ravioli.

Back in Benevento, traditional ricotta was a way to use leftovers from the cheese-making process, in which milk is heated and separated into curds and whey. The whey, which would otherwise go to waste, was heated again, and the result is ricotta (the word is Italian for “re-cooked”). These days, ricotta is usually just made with milk, and the process is simple: Heat milk, add acid (in Alleva’s case, citric acid, though you could also use lemon juice, vinegar or buttermilk), then drain. It’s easy enough to make at home, but Alleva’s distinctive heft comes courtesy of two extra measures. While most ricotta is drained only once, Alleva’s is strained several times through old-fashioned tin cans punched with dozens of little holes, meant to squeeze out all—and I mean all—of the excess whey. The second secret, and the one Bob’s most proud of, is the above-average butterfat content, thanks to his New York State-sourced whole milk. The minimum butterfat required for milk to be called “whole” is 3.25 percent, but what he uses hovers closer to 4 percent.

The result is a delightfully dense spread, a world apart from the watery, stabilizer-filled stuff in the supermarket. And unlike many ricottas, there’s no liquid pooling on top—Alleva’s is smooth and even throughout, with curds so tiny they almost blend together. The cheese, displayed simply in a plastic tub, is tinted a pale canary. “People always want their ricotta to be pure white,” he says, “but the butterfat gives it a yellow tint that means more flavor.” It’s perfect for eating plain, which is what his grandfather’s friends used to do outside the shop, “licking it off a spoon like ice cream.”

These days, the ricotta is made near Albany, in the heart of New York’s dairy country. But don’t picture some impersonal plant—the ricotta is custom-made by an upstate Italian-American family the Allevas have been close to for years. They run a commercial dairy facility but make Alleva’s ricotta on the side, using that great whole milk sourced from nearby farms. But fewer and fewer people come in for it. “Thirty years ago, this store was all cheese—no meats, no oils, no vinegars, none of that,” says Alleva. Now most customers walk right past the ricotta on their way to the flashy grocery display.

“These days, shopping for ricotta is an afterthought,” says Alleva, who grew up in Queens and has been working at the shop for over 30 years. While he sells about 4,000 pounds of mozzarella each week, only 200 pounds or so of ricotta gets delivered to Grand Street from Schenectady. People used to buy it for homestyle, classic recipes—like baked ziti or eggplant rollatini—but now, “thanks to all the cooking shows,” customers come in requesting an imported vinegar or honey to artfully drizzle atop their parmigiana. So six years ago, based largely on customer demand, Alleva expanded the store’s selection to include more imported items like pricey balsamicos and dried pasta with elegant curls. Do people who live in the neighborhood today come in? Not so much. “This whole area used to be more residential,” recalls Alleva, “but now that it’s so expensive, everything turned commercial.” Most of his weekday business comes from tourists. Of course, it’s been decades since Italian-Americans were the neighborhood’s main residents, but some still return: “The old-timers have their traditions,” says Alleva. “They come in from Long Island on the weekends and bring their kids and load up for special occasions.”

The storied shop’s future is uncertain. Alleva is a few years shy of retirement, and while his son occasionally drops in for a weekend shift on top of his full-time job, Bob says, “nowadays, the younger generation doesn’t want to work like this.” Still, he seems unconcerned when I ask if the shop is in danger. “We’ve had a nice 100-year run,” he laughs. “We’ll see what happens.”

Photo Credit: Rebecca McAlpin