We learned just before publication of this issue that Atla’s Conchas have decided to move their business to VT. Follow their journey on Instagram @atlasconchas.

One morning this spring, I set an alarm for 7am and rode a subway more than 100 city blocks for a carb. My eyes drifted shut as we rode over the Brooklyn Bridge, and when they opened again commuters piled onto the train at City Hall. Right, I remembered. People were on their way to work.

Me? I was on my way to eat conchas.

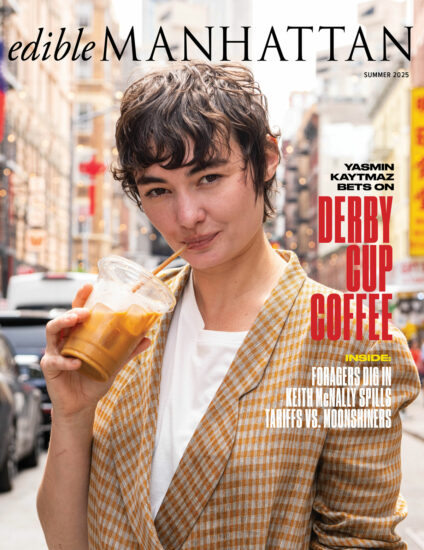

The pastry in question was a pale, brioche-like bun from Atla’s Conchas. It was crafted with a fine-tuned ratio of Appalachian flour to Sonoran wheat and it sported a pale, patterned crust made from small-batch butter. It cost several more dollars than the conchas around the corner, and I’d do it all over again tomorrow.

Until recently, I would have told you that conchas weren’t worth their weight in subway swipes; that pan dulce (“sweet breads”) were convenient sustenance; and that the best Mexican pastry was found in neighborhoods like Sunset Park and Jackson Heights.

Newer bakeries changed all that. And in recent years, Mexican American chefs have approached pan dulce like the Einkorn boule, experimenting with fermentation times, hydration levels, and new flavors. You’ll find cactus conchas and Oreo-studded orejas at these modern panaderías.

Atla’s Conchas is part of the movement. The owners, Caroline Anders and Mauricio Lopez Martinez, left behind baking jobs in suburban North Carolina last year to open a Mexican “microbakery” in Spanish Harlem.

They arrived without investors, press, or online hype—just a spot-on hunch. “We saw what was happening in other parts of the country,” Anders said. “We thought that conchas were about to have a moment.”

The conchas are based on a family recipe passed down from Martinez’s parents in Oaxaca. For decades, they baked pan dulce in a wood-fired oven they built themselves. “They were regular white flour conchas,” Anders said.

At Atla’s, Anders and Martinez are building on that tradition. They make conchas with Pennsylvanian white barley and cornmeal from Upstate New York. They grind those grains and several others into baking flour using a household mill no larger than a kitchen coffee grinder. Microbakery is right.

This process—known as full-inclusion baking—produces pastries of serious dimension and depth. Crunch into one of their conchas and you’ll catch notes of anise, yeast, and terroir. “It’s more nutritious,” Anders said of the milling process. “But really it’s a heck of a lot more flavorful, and that’s why we do it.”

One recent weekday, Anders was standing behind the counter when Martinez snuck up behind her with a tray of warm conchas for inspection. This particular batch sported a neat crosshatch pattern in various pastel shades, looking a bit like a family of sun-washed turtles.

“We don’t want too much color on the bottom,” Anders said, turning over a concha

flecked with sesame seeds. “You see? That nice light brown right there is what we’re going for. It still has some color around the edges.”

There are worse places to be at 8am than a hundred blocks from home.