In most cases, the sonnets written to the stalls of Saturday’s Union Square Greenmarket are studies on seasonal change: From spring’s duck eggs to winter’s watermelon radishes, many ingredients on offer are there one Saturday and gone the next.

But one decades-old, third-generation farm’s simple setup remains unchanged week after week, year after year: the fresh portobellos, criminis, white buttons and oysters-plucked within the past 24 hours and packed quiveringly fresh into plain brown paper bags-of the Bulich Mushroom Farm.

“Do you want to pick them? Or do you want me to?” Joe Bulich asks politely of the customer pointing to a few of his frilly oyster mushrooms. “You can do it,” she smiles, “I trust your judgment.”

And she should. From 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. each Saturday, Joe fills and weighs brown paper bags of his farmed fungus, exchanging pleasantries, money and mushrooms with customers. Dressed in earth tones, he could easily be mistaken for a city guy working a farmer’s stand for the hourly pay, but he’s a third-generation mushroom grower from the Hudson Valley-from which he and his mycelia left the farm at 4 a.m. for Manhattan.

We’re speaking literally: The Bulichs don’t forage in the forest or search through caves-though they do get asked about both fairly frequently. While other Greenmarketeers sell wild specimens like morels picked from the forest floor in spring or porcinis plucked come fall, this family trades exclusively in cultivated species.

The stand’s sign identifies them as New York State mushroom farmers, and there was time when that wasn’t a rarity. “There used to be about 40 mushroom farms in the Hudson Valley,” says Mike, Joe’s big brother. Together with Mark, the oldest of the clan, they run the operation that was started around 1950 by their grandfather, an immigrant from what was then called Yugoslavia. That decade saw a local boom in ‘shrooms, when the invention of the refrigerator rendered the ice houses lining the Hudson River obsolete-for ice, at any rate: Dark and well insulated with sawdust, they offered perfect conditions for another purpose: growing mushrooms. And so a new industry appeared nearly overnight, just like you-know-what after a heavy rain.

But by the early 1980s, the farmed fungus sector had all but collapsed. Large commercial mushroom operations that had popped up in Pennsylvania, cheap imported caps from China and rising fuel prices worldwide helped put nearly all of New York’s family-run mushroom farms out of business. And while a handful of tiny independent businesses are still at work, most of the older operations have turned from farming to distribution.

All except for the Bulichs, who today operate the last fully functioning mushroom farm in the state-thanks in part to Frank Bulich’s foresight in the 1980s, when the second-generation mushroom grower, unlike his fellow farmers, noted a coming demand for varieties other than standard white buttons.

The Bulichs began to experiment with shiitake, portobello, crimini and oysters, and after decades of selling to middlemen, they took a chance and began attending the then-new Union Square Greenmarket. This was long before “locavore” entered the lexicon, but customers came to covet the hearty, complexly savory flavors for salads and soups or risottos. Super-fresh-no rubbery stems or gummy caps here-they’re a far cry from those plastic-wrapped Styrofoam packs that change hands five times before your cashier rings it up at Key Foods.

“My father predicted correctly,” says Joe, “that the only farms that were going to make it would be the really small ones or the huge, commercial ones.” The Bulichs’ operation may be “really small” in comparison to those Pennsylvania giants, but they still harvest about four tons of mushrooms a week. The entire yield is grown in seven dark, temperature-controlled mushroom houses, which sit amid rustic tractors, utility sheds, an old-fashioned mini cement mixer, the family homes and the gorgeous rolling Hudson Valley hills and endless skies. It’s a lovely place, but as on all farms, the handiwork is hard.

Growing fungi is a multi-step, labor-intensive, time-consuming process that takes about 10 weeks per harvest. “You can make a lot more money working just 40 hours a week doing something else,” laughs Joe in one of the dimly lit mushroom houses: “A lot of people are just not cut out for it. We keep two crops going at the same time,” he says, a knife in one hand and a container in the other, “so we’re harvesting every day.”

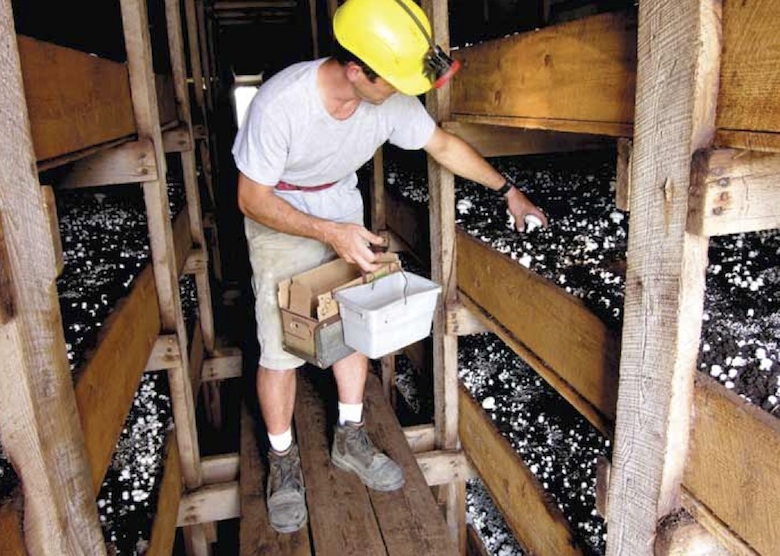

As he speaks he sports a coalminer’s hat, the beam of light shining straight ahead onto a bed of white buttons just beginning to “pin,” their little white dots poking up from the inch and a half layer of peat moss packed into the mushroom houses’ long growing beds. Five feet wide, the beds are made from hemlock, stacked several stories high-think condos for ‘shrooms-and stretch back into the darkness for 48 or 72 feet, depending on the house. Under the peat moss, which is meticulously prepared with water and lime in that old cement mixer, lies a layer of cured, pasteurized horse manure that the family brings in from just across the Hudson.

Joe says prepping the manure can take up to a week and a half, as it’s mixed with chicken manure and gypsum to manage the pH levels and nitrogen. By the time it’s loaded into the mushroom beds, the growing matter is a deep, rich black. Next comes a day-long high-pressure steam at 140 degrees, and once it’s cooled, Joe and Mark sprinkle on millet-size spores, as if seeding a lawn. They’ll germinate for 17 days before peat moss tops it all off.

Each planting yields four harvests, called “breaks”-the industry term for when mushrooms pop through the peat. After the last, the beds are cleaned and aired out, like a motel room for mycelium. The harvests are also sold to the Culinary Institute of America, to numerous distributors and of course at Union Square on Saturdays-along with discarded mushroom dirt the Bulichs call “bionic” soil. (Skeptics should check the farm’s sunflowers, which by late summer resemble streetlamps.)

And despite that hardcore harvest schedule, the family members themselves remain fixtures at Union Square: “Any time we can deal with the customer directly,” says Joe, “it’s better.” Customers, he says, know exactly where their fresh portobellos are coming from when they slice them into their spinach salad or sauté them into their fettucini or bake them, Bulich-family style, topped with sauce and cheese like a pizza.

Unless you’re Mark Bulich, that is. He’s one member of Bulich Mushroom Farm that-you guessed it-just won’t eat the fungi.

Photo credit: Nina Roberts.