New York has always been a thirsty city. Before we secured a safe supply of drinking water, beer surpassed both coffee and tea as the breakfast beverage of choice. The successive waves of immigrants who shaped the city’s history enriched New York with a highly social drinking culture, and by the early 1900s, German beer gardens, Irish pubs and Italian wine shops were fixtures in the city’s many ethnic enclaves, while highbrow bars in fine hotels and restaurants were becoming symbols of the city’s upper crust.

It’s easy to see why New Yorkers treated the 1920 Prohibition Act more like a silly suggestion than a federal law.

The nationwide “noble experiment” was billed as a way to reduce crime, increase health and safety and generally improve the morality of the masses. But the citizens of New York City didn’t buy it, and rather than abide by the ban, they set about subverting the laws. Organized crime syndicates set up networks to keep the city supplied with swill. Within five years, over 50,000 speakeasies had sprouted in the city’s streets—more than double the number of legal establishments that existed before booze’s banishment.

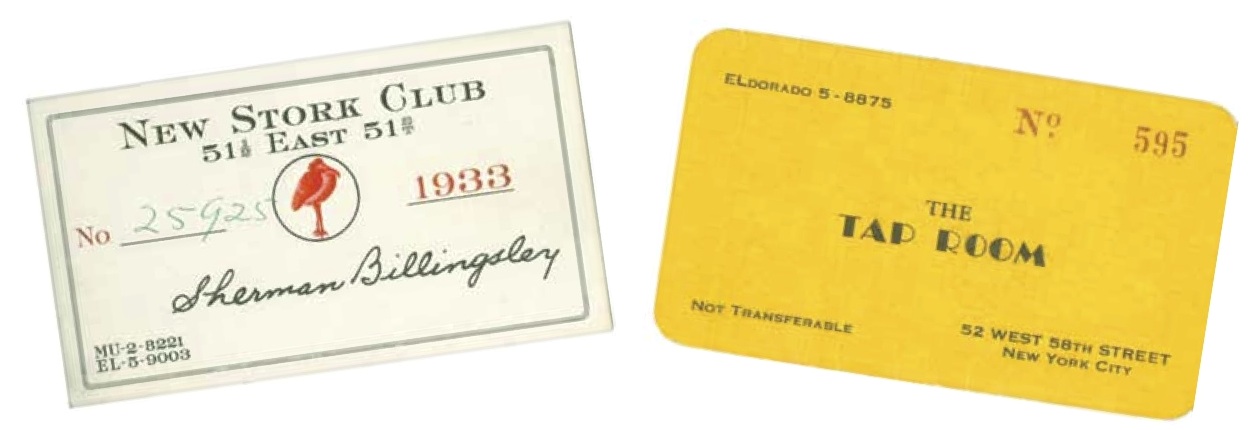

Prohibition was flagrantly flouted in New York—the mayor and the police commissioner were both known to frequent speakeasies. Yet these establishments were far from open to the public. Most issued membership cards, which prevented the federal agents from infiltrating these secret nightspots, while high prices ensured exclusivity. Famed speakeasy the ‘21’ Club charged $20—the equivalent of $200 today—for lunch. At most places, though, an illicit drink cost between 50 cents and a buck.

These days, establishments emulating speakeasies have sprouted on street corners everywhere, but for all their hidden entrances and hand-cracked ice, these bars are overlooking a key fact: Most drinks served during Prohibition were downright lousy. Contrary to the drink menus of modern speakeasies, the 1920s were not characterized by well-made Manhattans and Martinis. Most clandestine cocktails featured alcohol that was either homemade or adulterated with any number of “secret ingredients,” often in overly sweet concoctions designed to disguise the terrible taste of bootleg booze.

But unpalatable swill wasn’t the worst of it: Bathtub gin could be downright deadly. The surreptitious spirits were often made with poisonous wood or methyl alcohol, while toxins that masqueraded as drink mixers included creosote, formaldehyde, gasoline, chloroform, acetone and benzene. In 1927, there were 700 alcohol-related deaths in New York City, and an additional 1,200 were sickened or blinded by bad booze. So much for public health and safety.

Lucky for us, the utter failure of the “noble experiment” led to its repeal in 1933. Upon signing the amendment, President Roosevelt famously quipped, “This would be a good time for a beer.” No wonder he didn’t call for a cocktail.