Standing in the industrial-chic dining room of Barbuto, Jonathan Waxman, clad not in chef ’s whites but a T-shirt and sneakers, looks more like the rock star he once wanted to be than the culinary equivalent he became. Although other chefs have supplanted him as Greenmarket spokesmodels, in many ways he deserves credit for introducing New York to the farm-forward flavors that have taken modern menus by storm. Way back in 1986 the Times credited Waxman with transplanting what was then called “California cuisine” to our city scene, and his fresh-from-Chez-Panisse, ingredients-obsessed ethos would eventually blossom into the locavore revolution in full flower today. Along the way he inspired a next generation of chefs, including Bobby Flay, Aaron Sanchez, Joey Campanaro and Jimmy Bradley.

But growing up, he had his sights set on another kind of career.

“From the time I was in high school, ALL I wanted to do was play the trombone,” he says. “I didn’t care how or where, as a studio musician, on the Johnny Carson show.” A stint in the band Lynx left him stranded in Hawaii in 1972 when they broke up. “The only job options in Hawaii at the time for me were selling drugs or working in a restaurant.” He chose the latter, and discovered he loved it. When he earned his fare back home to California, the 23-year-old Waxman spent some time selling Ferraris by day and bartending at night while trying to figure out the next step. A class with Mary Risley at Tante Marie cooking school in San Francisco confirmed that he had found the only thing that could replace music in his life. “Mary suggested that I go to Europe for cooking school. She made me fill out the application and mailed it.”

Waxman arrived at the prestigious La Varenne culinary school in Paris on his birthday in 1975. When he finished the yearlong course, during which he was drilled in classic French techniques, his instructor told him a Relais and Châteaux property was hiring. He landed the job and spent a year at a Michelin-starred restaurant in a tiny French town where he did every job in the kitchen from butchering to making terrines and pastry.

Back in California in 1977, while working at a restaurant in Monterey, he got a call from Alice Waters. Her passion project Chez Panisse was only a few years old but its reputation was already enough to intimidate Waxman. “It was a terrible audition,” he remembers, shaking his head all these years later. “I got scared to death. I decided to recreate a meal I had at the Troisgros brothers [the iconic restaurant in Lyon]. It did not go well. Alice told me later that in the end, she hired me because she liked my handwriting.” Penmanship aside, Waxman’s recent training was just what Francophile Waters wanted in her counterculture kitchen—she herself had experienced a culinary awakening in France. And as the tiny restaurant forged in the smitty of its soul a new culinary consciousness, Waxman had a front-row seat: “At the time it was just me, Alice and Jean-Pierre Moulle,” who is the executive chef to this day.

But Waxman had his sights set beyond earthy Berkeley, and by 1979, with his 30th birthday approaching, he was itching to get to New York. He was Gotham bound when a fateful stopover in Los Angeles landed him behind the stove at Michael’s, the Santa Monica restaurant of “wunderkind” Michael McCarty that helped pioneer California cuisine.

“It was a really amazing time to be in L.A.,” he says. “There was this fervor for food.” He winces at how the foodie history books deem that era’s nouvelle cuisine—as absurdly precious, tiny portions that left people hungry. Rather he regards those years as reactionary and revolutionary, a time when cooks turned eating into an act both political and pleasurable, planting the literal and figurative seeds of the farm-centric moment so widely celebrated today.

“When I started cooking, everyone was using the same apple, the same zucchini,” he says of the commodity approach that ignored the individuality of ingredients. But cutting-edge cooks in California were turning that on its head and placing produce on center stage: “The renaissance was as much about the farmers as it was the chefs.”

As word got out that Waxman wanted the best and was willing to pay for it, purveyors beat a path to his door. “Farmers would bring me their vegetables, potatoes. I had this crazy guy who was a pilot for Qantas who would bring me boxes of John Dory from New Zealand. My duck guy hooked me up with a lamb guy. My network kept growing that way.”

But while produce-wise, California was a veritable Garden of Eden, Waxman couldn’t shake the jones for New York. In 1983 he arrived in style and opened the Upper East Side hotspot Jams, on East 79th Street, with partner Melvyn Masters (the name was shorthand for Jonathan and Melvyn). Florence Fabricant hailed Waxman as a “culinary comet” in the Times and his mesquite-grilled cuisine would draw a famed and famous crowd who paid a then-shocking $125 for a meal for two.

New Yorkers who still associated fine dining with old-world fare and formal settings balked at what seemed like big prices for small plates in a “California relaxed elegance” setting with an open kitchen that left them confused about where to look. But Waxman’s ingredient-driven, daily-changing menu was a revelation, from the salads topped with buttery medallions of lobsters, to the entrées like lamb, pompano, quail or veal saddle that were simply grilled and served with bouquets of vegetables. At a time when heavy sauce was de rigueur, Waxman laid his food bare, serving proteins dressed lightly in new-to-New-York flavors like lime-cilantro. Like a culinary missionary, he introduced such West Coast wonders as baked goat cheese medallions on mesclun with walnut-oil vinaigrette. (Mesclun was altogether unknown, and the greens sometimes baffled even the experts; in her New York Magazine review Gael Greene marveled at “an odd herb Jonathan described as purslane,” while Bryan Miller’s Times review said the menu “reads like a seed catalogue.”)

Indeed the California kid quickly adjusted to East Coast agriculture, embracing meats and root vegetables with a whole new enthusiasm and creating dishes like fragrant butternut squash and apple soup, winter greens and roasted beets. Back before the farm-to-chef explosion, fresh-from-the-soil carrots weren’t readily available, but André Soltner of Lutèce shared his sources, and over at the River Café in Brooklyn, Larry Forgione, known as the Godfather of American Cuisine, hooked him up with his local purveyors, including a chicken farmer whose birds became Waxman’s muse.

Jams’ pièce de résistance was grilled chicken with twice-fried potatoes, a dish Waxman had begun perfecting at Michael’s and which remains his signature to this day. He caused scandal by charging an astronomical $23 for the entrée—in 1984. “Those were amazing chickens” he defends, and they were: pastured poultry back when birds raised on green grass under blue sky were commercially nonexistent. Forgione had been working with Paul Keyser, a microbiologist turned farmer, to raise chickens outdoors; he used the phrase “free-range” to describe them—and now, decades later, so do the rest of us.

“It was all about those chickens,” says Waxman, though his recipe deserves a little credit, too. He boned each bird out, seasoned it with herbs, and grilled it split over hot flames of mesquite wood on a Montague Grill. When those intensely flavorful birds met the high heat, the skin crisped and the subcutaneous fat bubbled and the magic happened.

The vibe at Jams fit well into the whole Bright Lights, Big City ’80s excess when Wall Street was on a roll and Studio 54 was still a scene. “It was kind of crazy,” Waxman admits. “I would walk into the dining room and Andy Warhol would be at one table, Woody Allen at the next.” Also filling tables were culinary royalty like Julia Child, James Beard and Wolfgang Puck. He and Masters opened two more Gotham eateries, American bistro Bud’s and the French bistro Hulot’s, and a second Jams in London.

Before long the chef was not only feeding celebrities; he had become a bit of one himself, with a charming bad boy reputation. According to the late Michael Batterberry, founder of Food & Wine and Food Arts, “Whoever first used the phrase ‘rock star chef’ almost certainly had to have Jonathan in mind: The hair, the cars, the charm, the women. But also the extraordinary talent and bravado.” In the days before Twitter or even Food TV, Waxman was nearly as well known for his Ferrari, nights on the town and all-around indulgence as he was for his menus.

But when the money ran out, the party was over. After the market crash of 1987 those tender chickens became a tough sell, and Waxman shuttered Jams and his other restaurants. He sold the Ferrari, moved back to California, got married, had kids and went years without a professional kitchen to call his own. In 1991 he briefly opened Table 29 in Napa Valley, a 100-seat restaurant serving dishes like tomato-corn salad with citrus dressing and calves liver with pancetta and fries. “Hated it,” he says flatly of the wine country lifestyle. “I wanted to come back here,” he says.

So 1993 found him back in New York as a consultant with the Ark Restaurants Corporation opening restaurants like the Bryant Park Grill, where he hired Joey Campanaro and Jimmy Bradley. “Jonathan’s brain works in the opposite way of most chefs, says Bradley, now of the Red Cat and the Harrison. “He lets the food talk to him rather than dictating his vision on the ingredients. He’s like the vegetable whisperer.”

While the corporate gig allowed Waxman dinner with his family, he was soon ready to have his own place again. In 2002 he opened the acclaimed-but-short-lived Washington Park, in the spot that now houses Cru. Dishes like sweetbreads with chanterelles; slender haricots verts and warm wild mushroom salad with buttery chunks of lobster received rave reviews but the restaurant quickly closed.

In 2003 he went to look at a space on Washington Street in the way West Village, and took his old friend Jimmy Bradley. It had been built as a garage and they both thought the cement floor and garage door were just plain ugly. “It just wasn’t what I expected for Jonathan,” recalls Bradley. “He has such an elegant eye and style.”

But Waxman overcame his initial hesitation about the space. The cement floors, glass wall and tiled white kitchen are a departure from his past venues, with their straw-colored walls, luxury linens and elegant table settings. No tablecloths or fancy presentations here, just the clean cuisine Waxman has long since mastered, this time with an Italian accent. (Like Waters, Waxman’s culinary muse is now Italy, not France. Barbuto is Italian for “bearded,” a wink to the whiskers sported by both Waxman and business partner photographer Fabrizio Ferri.)

These days, access to breathtaking ingredients doesn’t require a letter of introduction. Thanks in no small part to the dirt-devoted doctrine Waxman brought here 25 years ago, fresher fare is now downright abundant. (Though modern eaters tucking into the menu’s Bell & Evans birds might wish they could have tasted that almost-wild outdoor experiment). That signature chicken recipe has modernized a bit as well; the fowl meets its fate not over mesquite flames but in Waxman’s unique oven, which boasts multiple heat zones.

Much of the menu which changes daily, and may include thin-crusted pizza bearing pancetta and taleggio; fettuccini with wild boar ragu; an unctuous carbonara slicked with egg, Parmesan and black pepper; or pan-fried monkfish with farroto and butternut squash. The vegetable whisperer lets the Brussels sprouts decide to be shaved thinly and tossed with Pecorino Romano and lemon; hears beets beg to be roasted and served atop faro; and actualizes the squash’s aspiration to be feather-light gnocchi. Barbuto’s tightly curated dessert menu includes wondrous affogato, a scoop of gelato drowned in espresso.

And in contrast to the days of serving supper to Andy Warhol and Woody Allen, the crowd at Barbuto is more diverse, something the older family man Waxman revels in. While the celebrities and foodies flock for his food, some of his favorite customers are families that come in with their kids. “And we have this neighborhood couple in their 90s,” he grins. “They come in every week for chicken and martinis. I love that.”

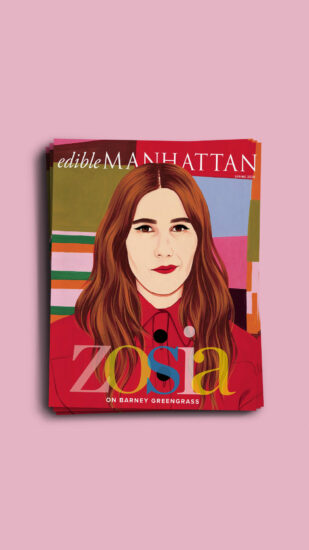

Photo credit: Michael Harlan Turkell