Time was, cider in upscale restaurants meant just one thing: Martinelli’s sparkling, a non-alcoholic way for kids to join a toast when their elders raised a glass of Champagne. So why are waiters at top tables all over town proudly presenting epicurean adults with, of all things, a cider menu?

If you’re at Terroir in the East Village, there are probably a dozen on the list; at Gramercy Tavern, even more. But these artisan offerings are a far cry from the oversweet Champagne stand-ins of yore. Today, a generation of grown-up drinkers have made cider—the fermented, alcoholic kind, increasingly crafted from local heirloom apples—a must-have for many prestigious wine lists.

“There really is a sizable cider population,” says Carla Rzeszewski, who runs the beverage programs at The Breslin, The Spotted Pig and John Dory. “They come in asking for cider, they are very familiar with all the local cideries and they are very interested in supporting the local movement.”

Northern Spain and France and the West Country of England have had strong cider traditions for centuries and Rzeszewksi offers ciders from Normandy, the classic region in the north of France famous for its apple-based alcohol. But she also stocks new bottles from young producers like Eve’s and Slyboro in upstate New York.

“We don’t have to handsell them at all,” says Amanda Reade Sturgeon, wine director at Dovetail on the Upper West Side. “They’re not super-expensive; they’re easy for people to try out.”

“It helps that the value is so tremendous,” agrees Juliette Pope, beverage director at Gramercy Tavern. “The prices for such quality in these ciders is incredible. So guests can’t really go wrong, especially since they can taste any of them before committing, as with our wines by the glass.”

Terroir does the same with some of their ciders—higher-priced specialty bottlings from Farnum Hill, for example—and at The Breslin Rzeszewski has cider on tap, making samples easy.

Cider has been part of the program at Hearth and its affiliated Terroir wine bars for several years, but 2012 was a tipping point, according to David Paul Flaherty, Hearth’s beer director (see p. 66) and self-proclaimed “Cider Warlock.” In the past, he had to get the staff worked up about their offerings to really move them. “This year in particular we didn’t have to do anything,” he said. “Where is this coming from?”

Craft beer grew up in specialty bars and then moved laterally into restaurants; cider seems to have done the same thing only faster, thanks to the passion for all things locavore and the entrepreneurial inspirations of orchardists across the Northeast. Almar Orchards in Michigan created J. K. Scrumpy’s, a leading cidery, for just that reason, according to co-owner Bruce Wright. Wine led the way for added-value agricultural products, and cider gives apple growers a grip on that more profitable model.

Hard cider first saw a blip of popularity—or at least attention—as an addendum to craft beer, in a simple, often sweet style; today the options are diverse. Not as diverse as wine or craft beer—there are fewer than 100 serious cideries in the United States, compared to more than 2,100 craft breweries—but enough that cider can be explored rather than simply consumed. “I really see a lot of diversity of styles locally,” says Flaherty. “Everyone is playing and experimenting.”

With so many to choose from, it’s good to get some guidance. Rzeszewski sometimes translates ciders into wine terms: “For example, suggesting that the Sow the Seeds is similar to a Pinot Grigio–style cider, whereas the Scrumpy’s may be more similar to an off-dry Riesling.”

“If a cider has oxidative qualities, we compare it to sherry,” says Alexis Kahn, co-owner at ABV on the Upper East Side. “If a cider is well-carbonated, and has a touch of sweetness, we compare it to a prosecco. People are becoming more accustomed to finding funky flavors in wine, so it’s becoming a little easier to sell cider.”

That’s true beyond the gastropub and wine bar scene, and not just to wash down New American cuisine. Macelleria, the Italian steakhouse in the Meatpacking District, serves bittersweet cider from Eve Cidery in Ithaca and has been participating in the Glynwood Center’s annual Cider Week consciousness raising for a couple years even though cider doesn’t have a strong Italian connection.

“We use it as an option for sparkling wine,” says owner Violetta Bitici. “People love the New York State connection, and it doesn’t have a strong apple flavor.”

Rzeszewski sees lots of reasons to keep cider on the list year-round. “Cider is a treat to pair with food. The pairing is the easy part; the work lies in inviting a table otherwise unfamiliar with cider to accept a new idea. I think the menu at The Breslin and The [Spotted] Pig are made for cider. That sweet suckling pig on the chef’s table at The Breslin is begging for a richer-style, fruit-forward cider.”

It could be argued that the popularity of pork would be reason enough for keeping a cider or three on hand. At Macelleria Bitici has paired it with porchetta, charcuterie and crostini with lardo, as well as with Mele e Maiale—“Apples and Pork”—a dish that almost calls for cider explicitly.

But pig pairings are just the beginning. “We always like to suggest pairing our ciders with cheese,” says Kahn at ABV. “We have a rotating selection of domestic farmstead cheese and the acidity and light body of the ciders make them very versatile with a range of cheese styles.”

Beth Griffenhagen at Murray’s Cheese couldn’t agree more; they recently offered several cider-and-cheese pairing classes. “The acidity cuts through fattiness in cheese, and the sweetness balances salt. Carbonation of any kind is great with cheese and really breaks up the creaminess on the tongue, which is one reason beer also pairs so well with cheese. Lighter alcohol makes it more versatile for pairing with cheese than wine, and the fact that it has some tannins, which play off fat, but not nearly as much as wine.” According to Griffenhagen, classic cider pairings are of the “grows together, goes together” sort—Camembert with Normandy ciders, Cheddar with West Country English styles—and she notes that many upstate ciders go well with delicate, bloomy rind cheeses.

Variety, quality and pairing potential are all well and good, but for wine directors (and their bosses) the bottom line is cider has become popular enough to pull its weight in terms of turnover and sales. As in most New York apartments, competition for space is intense in the city’s wine cellars. At Dovetail, Sturgeon says she had more ciders before but ran out of room; Flaherty says Hearth moves enough cider that he could sell 20 rather than just a dozen if he had the space.

While demand for quality local products and creative orchard owners responding to overseas competition may be practical reasons for cider’s rise, Flaherty thinks there might be a more abstract base to cider’s newfound appreciation. Given that cider was the daily drink of America’s settlers, from the Puritans down to the Founding Fathers, “I think what’s happened is, in a strange way, it’s built into our DNA,” he says. “This is really America’s drink.” •

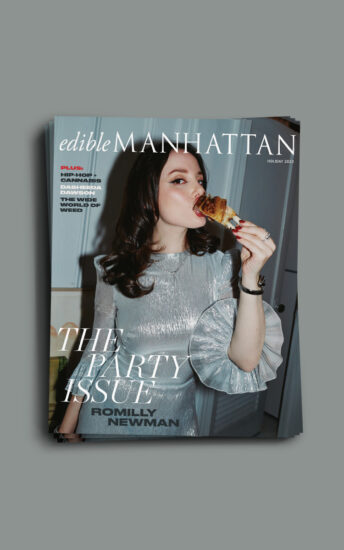

Photo Credit: Scott Gordon Bleicher